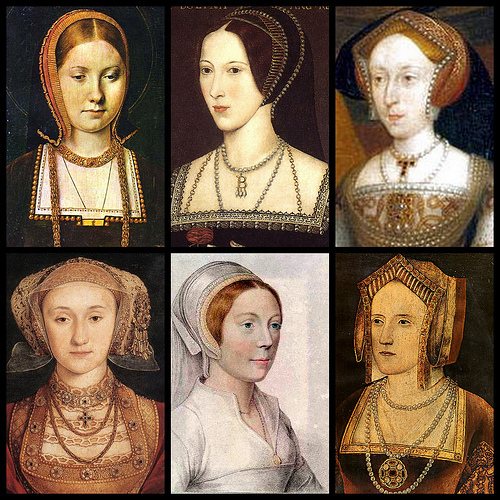

The issue of succession has been a problem for all hereditary monarchs, but one king in particular seemed to have more than his share of bad luck. Henry VIII is famous for how many wives he had, and had killed. His fame is not due to his number of wives,. since many kings have had many wives, but because he is peculiar to his age. Henry VIII reigned in late Medieval England where good Christian kings had only one wife their whole lives. Therefore, Henry is the exception to his age and this is one of the things that makes him so interesting.

Why was Henry so obsessed with succession? Well, after the War of the Roses, the kingdom of England had united the two warring houses of York and Lancaster by marriage under Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of York. Their second son was the eventual King Henry VIII. Thus, Henry embodied the reunification of England and that idea could only be preserved through the birth of a male heir.

When Henry’s older brother Arthur, the Prince of Wales, died, Henry was named heir apparent and married his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, on the grounds that the prior marriage had not been consummated. The marriage was a happy one until it became obvious that Catherine could not fulfill her marriage duties.

In Medieval Europe, the one and most important job for a queen was to produce an heir to the throne to ensure the continuation of the dynasty. Not only was this an issue of family pride, but national security. If a king died without an heir, he would leave a power vacuum which would often lead to civil war. Since Henry embodied the reunion of the realm after the War of the Roses, he was determined to make sure that a safe line of succession was ready for his dynasty. Unfortunately for Catherine, she only bore Henry one daughter who they called Mary. Henry began to reflect and worry. During his musings he stumbled upon the verse in Leviticus 18:16 which warned men of God not to marry the wife of a brother. He then decided that God had punished him for marrying his brother’s wife and asked the Pope for a divorce, despite Catherine’s protestation of celibacy prior to her marriage to Henry.

Henry sent Cardinal Wolsey to Rome to represent him to the Pope, but the Cardinal failed to secure the divorce. By this time, Henry had become estranged to his wife and had set his eye on the beautiful and ambitious Anne Boleyn. His hands tied by the Pope, heart run away with Ann,e and mind feeling the pressure of succession, Henry hit upon a solution to his problems that would change England forever.